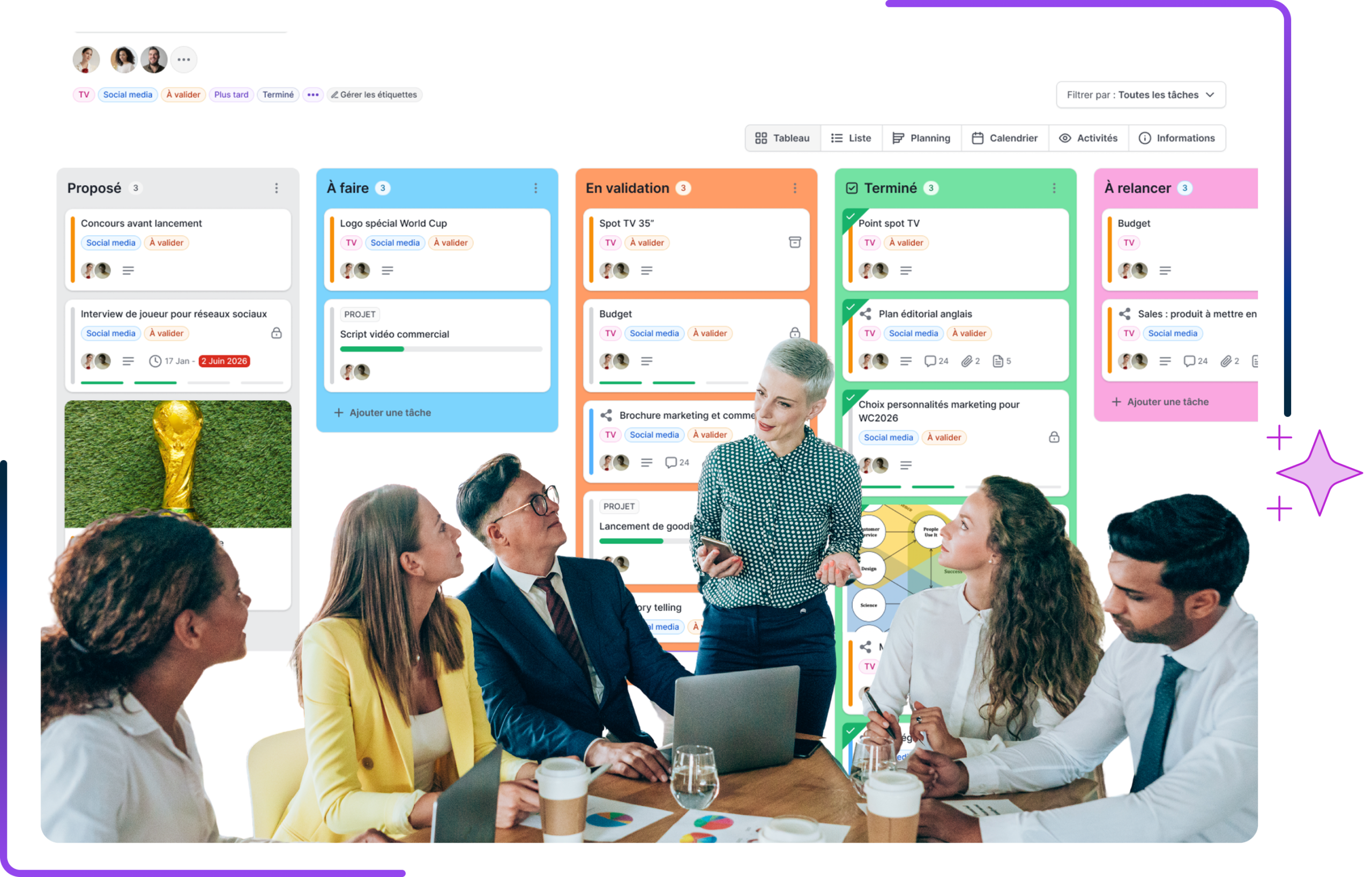

Informer. Structurer. Collaborer. Connecter.

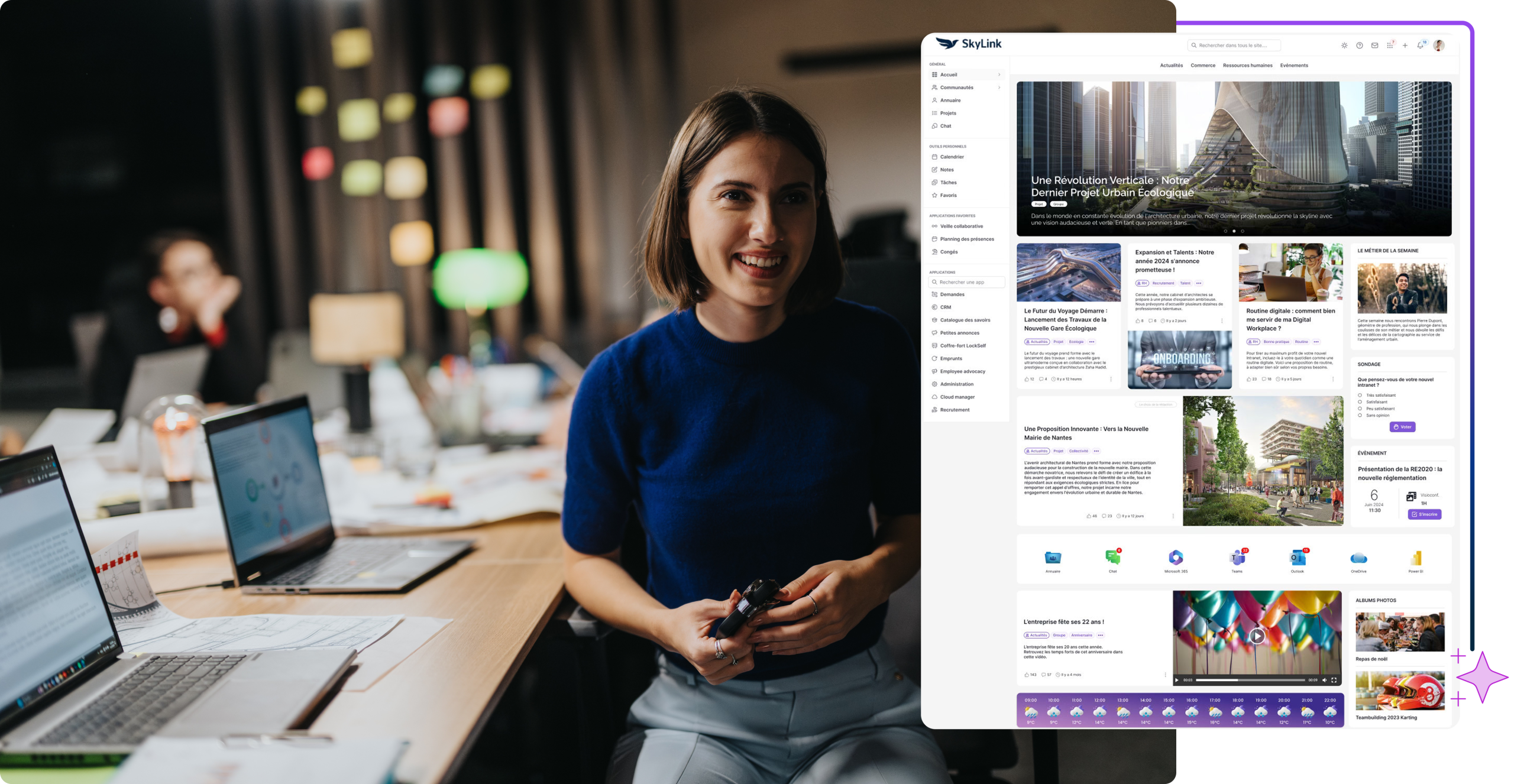

La plateforme qui s’adapte à vos usages,

à vos secteurs d’activités

pour accélérer votre efficacité.

500+ clients

2.3M+ utilisateurs

80+ partenaires

Informer et fédérer durablement tous vos utilisateurs.

Connecter vos publics externes à vos informations et services.

Travailler ensemble efficacement, au quotidien.

Capitalisez vos savoirs, enfin actionnables et augmentés par l’IA.

Construire une expérience collaborateur cohérente, sans dépendance ni complexité inutile, en réunissant vos usages sur une plateforme unique.

Plus de 2 millions de collaborateurs utilisent Jalios au quotidien